Blocked Tear Ducts – Kids (Probing/Tubes)

The tear (lacrimal) glands produce tears constantly during the day to keep the eyes lubricated. The tears drain away from the eyes through the lacrimal drainage system. Approximately 7% of infants are born with congenital obstruction of the tear drainage system in one or both eyes. This percentage is even higher in premature infants.

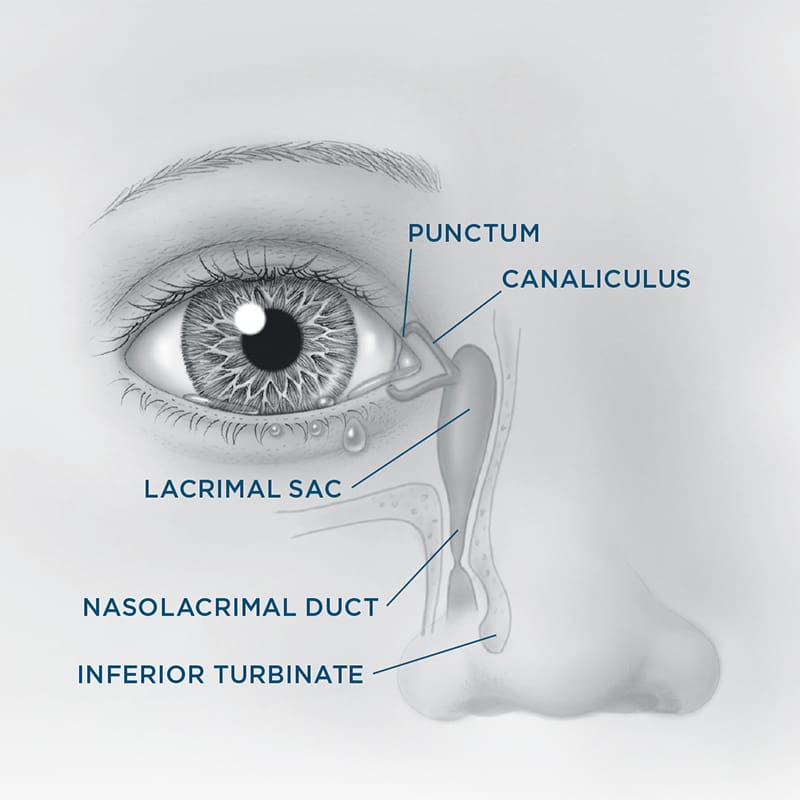

The tear drainage system starts at tiny openings in all four eyelids called puncta. Each punctum leads into a small tube called a canaliculus, which in turn empties into the lacrimal sac, located between the inside corner of the eye and nose. The lacrimal sac leads into a canal called the nasolacrimal duct. The nasolacrimal duct passes through the bony structures surrounding the nose and empties tears into the nasal cavity.

With each blink, the eyelids push tears evenly across the eyeballs to keep them lubricated and healthy. Blinking also helps get old tears into the lacrimal drain system. Once tears are inside the drain system, blinking acts like a pump to push those tears from the lacrimal sac down through the nasolacrimal duct and into the nose.

The most common symptoms of a blocked tear drain are excessive watering, mucous discharge, eye irritation, and painful swelling in the inner corner of the eyelids. Newborns with congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction may have a blockage anywhere along the tear drain system. Usually, the blockage occurs at the end of the nasolacrimal duct, where a thin membrane can block the tears from emptying into the nose. If the nasolacrimal duct is blocked, tears will back up, spill over the eyelids, and run down the cheek.

Tears can also be trapped in the lacrimal sac, leading to an infection. A skillful history and physical examination can usually pinpoint the cause of tearing.

It is important that children with excessive tearing be examined by an ophthalmologist to determine the cause of the problem. In some children, excessive tearing may be due to causes other than tear duct obstruction.

Treatments

Initial treatment involves massaging the area around the affected lacrimal sac to force the tears down the nasolacrimal duct, and to push open the membrane causing the obstruction. The physician may also prescribe oral antibiotics, drops, or ointment. Most congenital tear duct obstructions clear with conservative measures by one year of age.

If massage does not relieve the tearing, additional treatments might be necessary. Your child’s physician may be able to open the blockage by inserting a thin metal probe through the punctum and down the nasolacrimal duct into the nose. This outpatient procedure may take place in the office or in the operating room.

For severe or recurrent cases, additional options include physically dilating the nasolacrimal duct with a balloon, propping the nasolacrimal duct open with a temporary silicone stent, or surgically creating an alternative drainage pathway for tears to pass into the nose.

Most patients experience resolution of their tearing and discharge after treatment is completed, with little if any postoperative discomfort.

Risks and Complications

Bleeding and infection, which are potential risks with any surgical procedure, are very uncommon. Minor bruising or swelling may be expected and will likely go away in one to two weeks. Occasionally, the body may form scar tissue that blocks the drain again, which may require additional procedures.

Your child’s surgeon cannot control all the variables that may impact your child’s final result. The goal is always to improve a patient’s condition but no guarantees or promises can be made for a successful outcome in any surgical procedure. There is always a chance you will not be satisfied with the results and/or that your child will need additional treatment. As with any medical decision, there may be other inherent risks or alternatives that should be discussed with your child’s surgeon.